The Other Legacy of Arthur Ashe

December 4, 2019 | By Diane Bezucha

Arthur Ashe Institute CEO Marilyn Fraser (left), Fordham University Associate Professor Christina Greer (center) and SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University VP Keydron Guinn at Wednesday’s 27th Annual Arthur Ashe Memorial Lecture, where Greer was keynote speaker. Photo by Diane Bezucha.

Many sports fans know Arthur Ashe as the only black tennis player to win men’s singles at the U.S. Open, Wimbledon and the Australian Open, but his work off the court left another legacy.

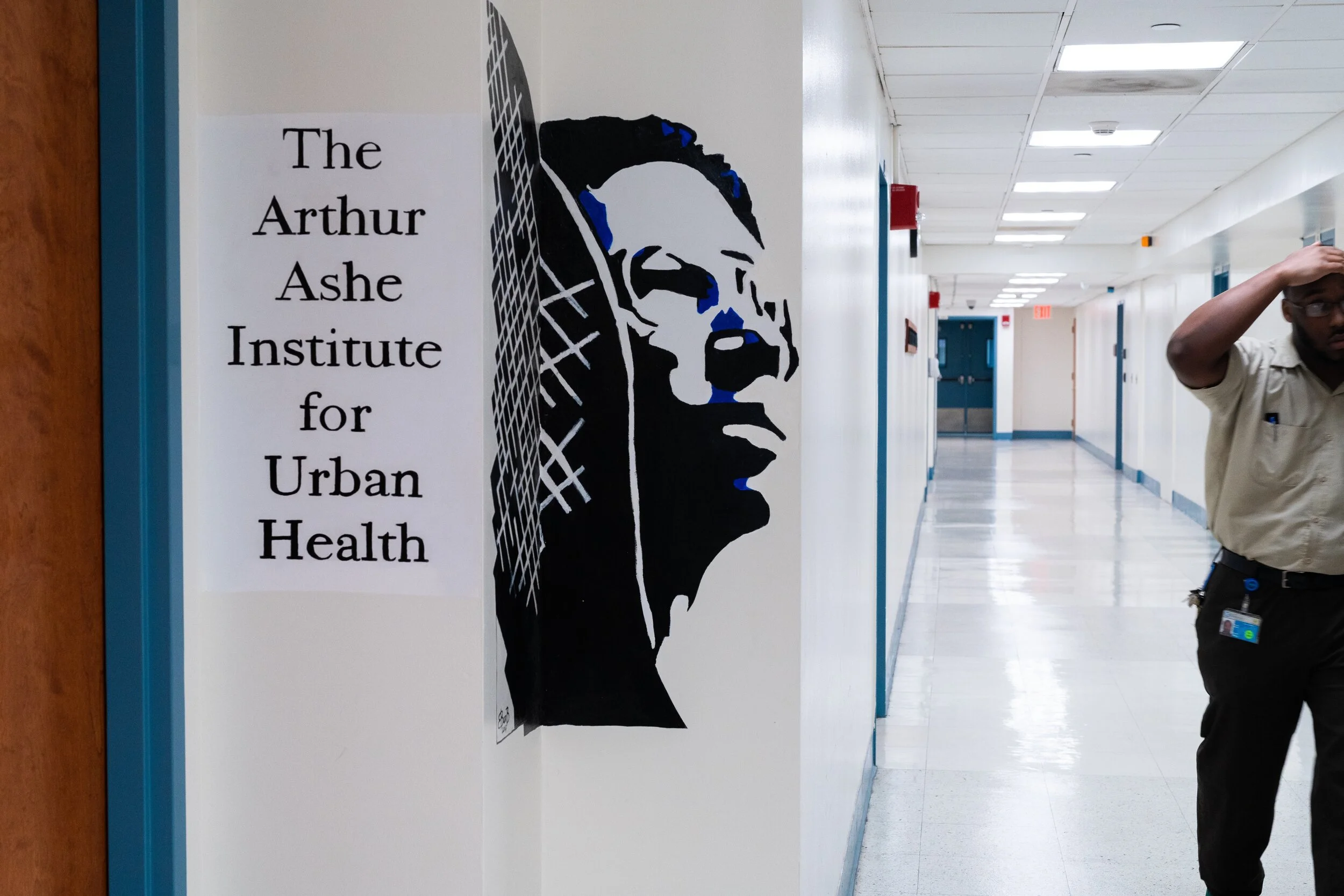

After contracting HIV from a blood transfusion, Ashe became a champion for healthcare equity in low-income and minority communities, founding the Arthur Ashe Institute for Urban Health just two months before his death in 1993.

Today medical professionals and community partners gathered at SUNY Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn to celebrate the Institute’s 27th anniversary and examine Ashe’s legacy in the current political climate.

“There is no time like the present to justify the existence of an organization like the Arthur Ashe Institute,” said Ruth Browne, the institute’s former CEO who now heads Ronald McDonald House New York.

With affordable healthcare at the forefront of the 2020 presidential election, issues of health disparity in low-income communities are finally being addressed on a national stage.

According to research from the Kaiser Foundation, black communities experience HIV and AIDS diagnosis and death at rates seven to ten times that of white communities. Poor communities still suffer from higher rates of asthma, high blood pressure and diabetes. And these same communities face greater disparity in housing, education, environmental quality and social services.

“All these things should be taken as a collective,” said Christina Greer, the keynote speaker and Associate Professor of Political Science and American Studies at Fordham University. She encouraged policymakers and voters to keep health disparities at the forefront of their decision-making process, as they are often indicators for other social inequities.

While some people point to successful universal healthcare systems in European countries as the answer, Greer does not think this is a fair comparison.

“For the United States, single payer systems are a problem of scale,” said Greer. There are no European countries that are as big or diverse as the U.S.

Greer admits she doesn’t have the answer to the healthcare question, but she is confident a solution exists.

“We can figure it out, but it’s about who is at the table to say what works, ” said Greer. “I’m tired of having this conversation about what poor people need, when no poor people are here.”

And this is something the Ashe Institute believes in as well. Their program model includes partnerships with public schools and healthcare organizations to create pipelines for people of color to enter medical professions and engage in healthcare policymaking. And for years the Institute has built relationships with Brooklyn barbershops and hair salons as hubs for community-focused health education.

As a political scientist, Greer believes that change also comes through the voting booth. But beyond simply voting, her advice is to invest in the people and organizations, like the Arthur Ashe Institute, who are doing the real work. She calls it a “political tithing” and said even five to ten dollars a month can make a difference.

But for anyone who cannot make a financial commitment, Greer offered the advice she gives her students: take a break from your television show for five minutes and “educate yourselves.”

This is a sentiment Ashe would support. In his words, “Start where you are. Use what you have. Do what you can.”